22. Perspectives.

On processes and projects.

Dear friends,

This month, I acquired 石をつむ (Laying Stones), a photobook for which I had been searching a long time. I’m excited to write a little about it in this newsletter. But first, I would like to give you some insight into my creative processes by discussing a project I am just starting to work on.

Let’s dive in.

In issue 20 of this newsletter, I wrote about my exhibition of Kanda, 20 April 2021. For that project, I photographed a street corner from a fixed camera location over many moments of time. By so doing, I hoped to make a detailed study of a subject while investigating the notion that a single photograph can be decisive.

Reviewing the project got me to thinking: what might I achieve the same thing if I flipped the process, and instead photographed a single moment of time, but from multiple locations?

Technically, Kanda, 20 April 2021 had been an easy project. The main requirements were time, a lot of patience, and a comfortable pair of shoes. This new project (which still needs a name!) is much more complex.

I am using multiple cameras triggered with a radio transmitter and receivers, a system that I pieced together myself (and that works correctly only about half the time). For each camera, shutter speed and focus must be preset manually, so the shutters can release simultaneously when triggered.

Beyond the technical matters, it is necessary to find a location where I can set up the cameras at different angles, where there will be enough people passing, yet where I won’t be in the way. And, since I can’t be behind more than one camera, I have to mentally visualize what each one will capture when deciding the moment of exposure.

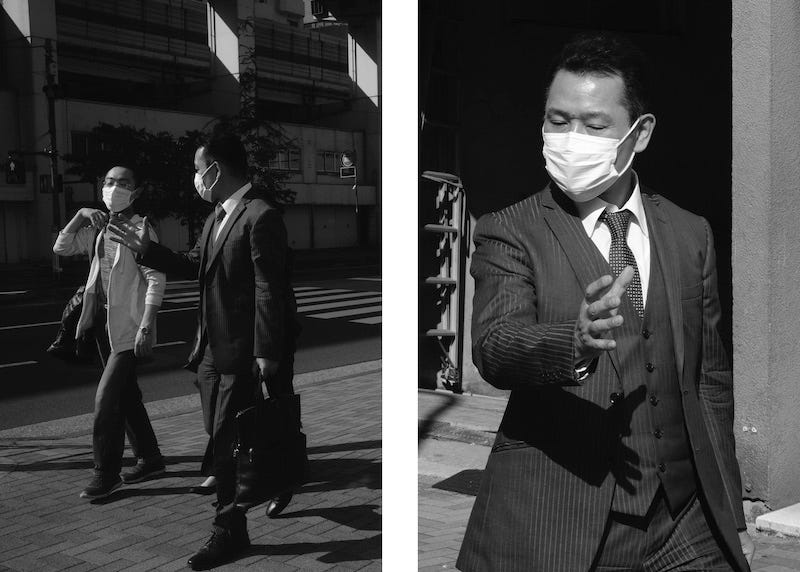

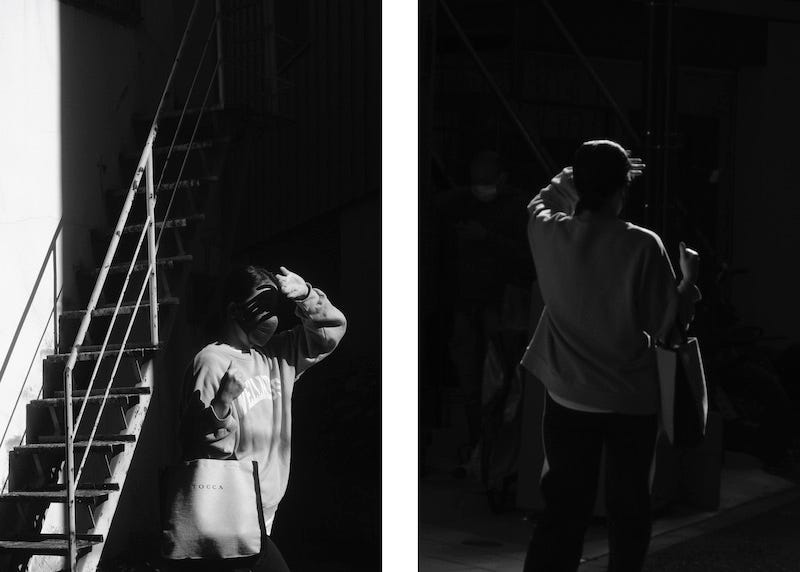

I am unaware of this approach ever having been taken to candid street photography before. As such, I don’t have a particular intention for the photographs; I am doing this to see what might be revealed.

So far, I find something uneasy about looking at the resulting photos. I suspect that it partly stems from the fact that it is unnatural to see the same moment from multiple angles. It may also be because these photographs remind me that most modern city-dwellers are under a state of constant surveillance.

But there are more constructive aspects as well. As I look at each pair of photographs, my eyes begin moving back and forth, comparing even the smallest details. So, they encourage me to be a more careful viewer.

Moreover, the differing realities in the paired photos emphasize the importance of viewpoint and context, and that the photographer is never a neutral observer, but a maker of decisions.

Should I ever print and show this project, the manner of presentation surely will be important (as it was with Kanda, 20 April 2021). I like the diptychs I am showing here, which give equal weight to each photograph. I can also imagine having photographs of different sizes, or presenting them at some distance from each other.

But before dealing with any of that, I’ll be taking more photographs. For me, November and December are the best months for photography in Tokyo, with the low mid-day sun. I'm hoping that with this project I can take full advantage of it.

I would love to hear what you think! If you have reactions, please don’t hesitate to drop me a line.

I have a special interest in photobooks that deal with the subject of grief and mourning. It is something that Japanese photographers address more often, and more directly, than their western counterparts.

Following the 2011 tsunami in Japan, thousands of personal photographs began to be found among the wreckage. Photographer Munemasa Takahashi joined a project to restore the photographs, identify their owners using facial recognition and other technology, and return them. During this period, he largely stopped taking photographs for his own personal projects.

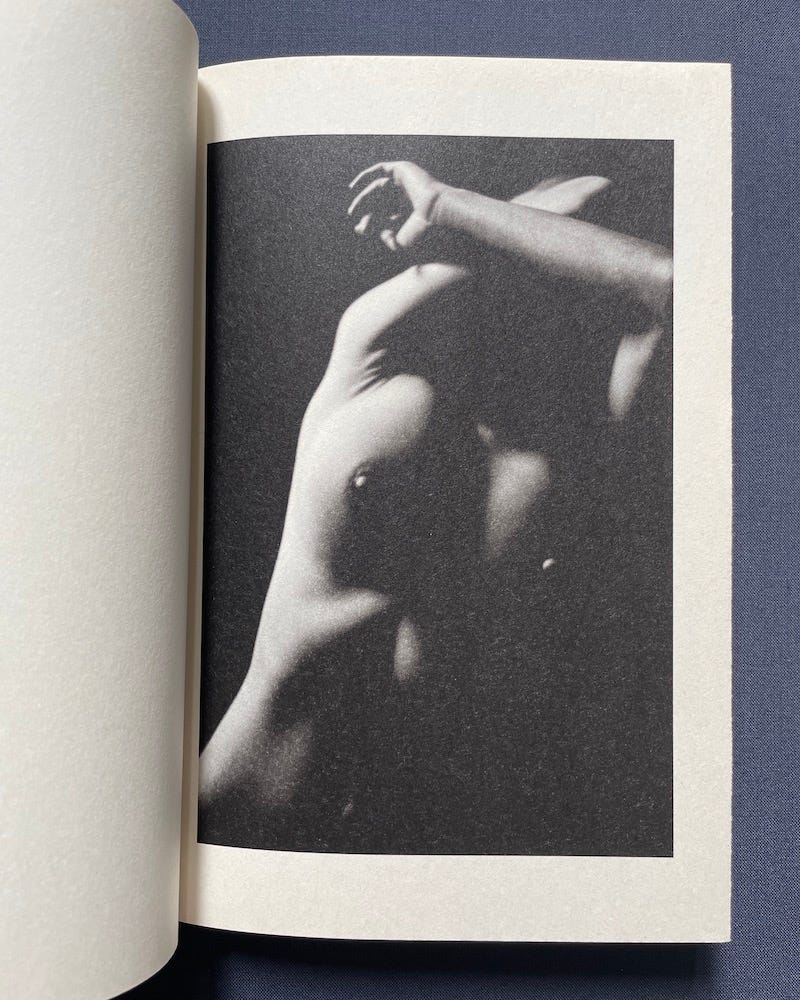

But after the death of a close friend, he felt compelled to begin photographing again, as a way of processing his grief. He writes that, “I started to take photographs of flowers, plants, the light and the body, which those subjects that will face the end and regenerate in a different form.”

Those photographs eventually took shape as a self-published photobook, 石をつむ (Laying Stones). I became aware of the book through an exhibition of Takahashi’s work at PGI, surely one of the most prestigious photography galleries in Tokyo. Although 700 copies were published—a remarkably bold run for a self-published book—they sold out and have been virtually impossible to find. I even reached out to Takahashi, but he was unable to suggest where I might still obtain one.

This month, in a small bookstore on the backstreets of Ebisu, I finally came across a copy. Although it was listed as new, the packaging was open and the first page was dog-eared. No matter. I’m thrilled to have it.

Japanese photobooks that deal with grief often overflow the expected forms of the medium. I am thinking about Sakiko Nomura’s Fate in Spring, which has the tall, narrow dimensions of a Buddhist prayer book, and the loose, unbound pages of Hajime Kimura’s Snowflakes Dog Man. It is as if the photos alone are not enough, can not be enough, to express the author’s emotions.

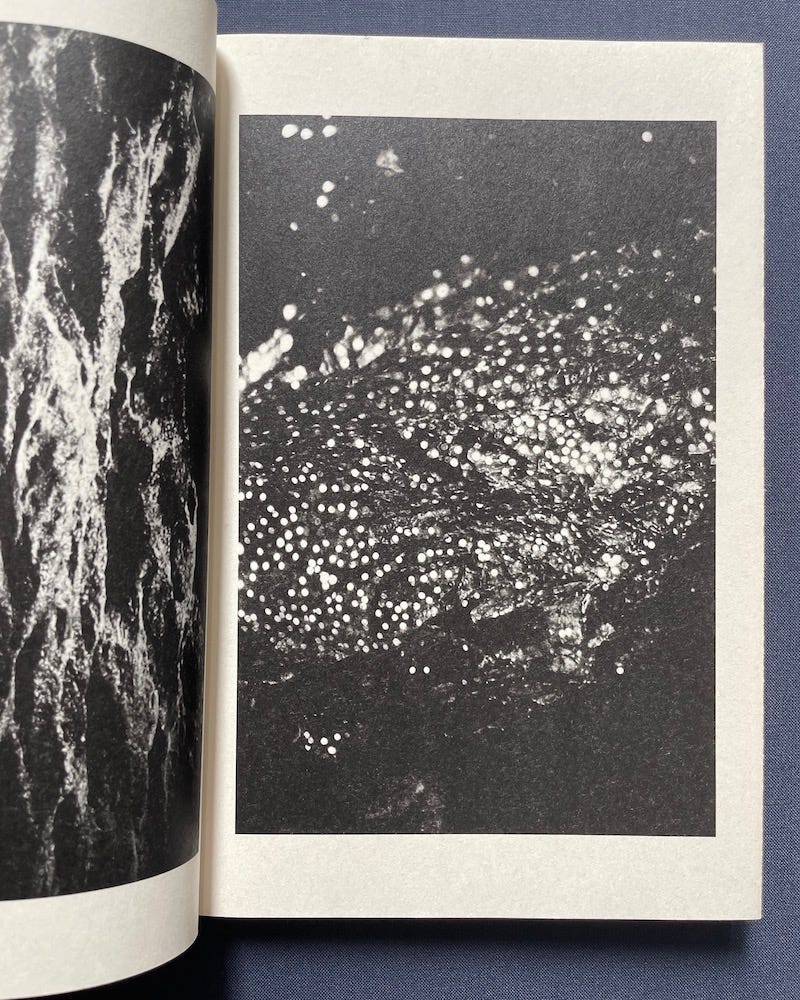

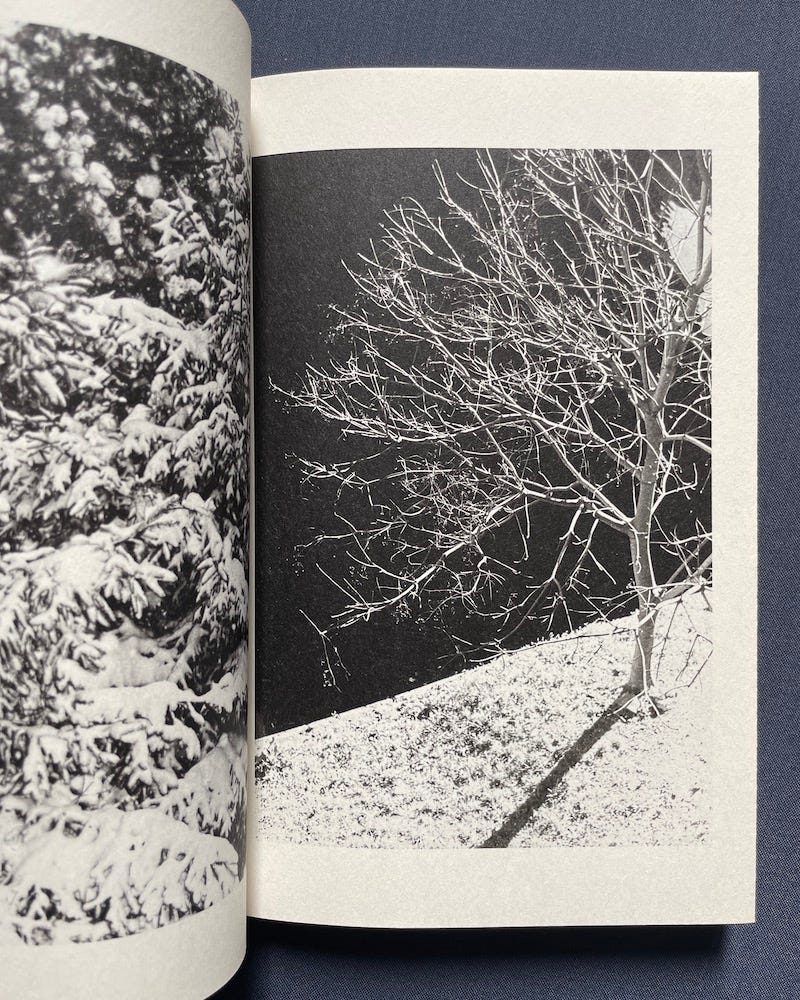

Laying Stones is no exception. It has no cover, no title page, no colophon. (An accompanying pamphlet provides the necessary information.) Its 80 pages are bound with a traditional four-hole binding. The matte printing is somewhat flatter and less detailed than his gorgeous prints, yet has a tactile feel that perfectly suits this project.

Takahashi is equally adept at photographing abstracts, landscapes, and nudes. The photos are contemplatively sequenced, suggestive of an emotional journey that begins with loss and confusion. Among books in this genre, Laying Stones is notable for the sense of peace that comes at the end.

Moving forward in time, Munemasa Takahashi’s latest book is 糸をつむぐ (Spinning a Yarn). Inspired by his friend who had died, as well as by the photographs he recovered following the tsunami, he began a project photographing things that float on water. As he continued working on it, he had a child, and he began to make unexpected connections between the photographs in the project.

“Photographs straddle over multiple timeframes,” Takahashi writes of this new work. “Every time you look back, episodes are newly connected or separated, continually spinning the narrative into the future.”

If you’re interested in Takahashi’s photography, Spinning a Yarn can still be found easily in Japanese bookstores, and its price is very reasonable. I recommend looking into it.

Finally, a note for photo enthusiasts who live in the Tokyo area. The Fujifilm Square Photo History Museum is currently holding an exhibition of Issei Suda’s Landscapes of the City, Margins of the City, a series that that has been largely forgotten since Suda exhibited it in 1986. Suda is generally known for his black and white snapshots, but these are medium format photos taken on color reversal film and they are absolutely stunning. The show runs until December 28, and may quietly be the best one in Tokyo this year.

The brochure accompanying the show notes that, when asked about his photography, Suda said, “When I was taking photographs I was always surprised by how interesting things could look if you varied the angle a little.” It was nice to find that bit of synchronicity between Suda’s processes and my current project.

I hope that you enjoyed this newsletter!

Over the next month, I’ll be busy working on an exhibition of my own that will take place early next year. I plan to preview that for you in the next issue.

If by chance you haven’t yet subscribed, here’s a button:

Thank you for reading,

Joel