36. moment

Yasuhiro Ishimoto

Dear friends,

Of all the photobooks on my shelf, the one that haunts me most is Yasuhiro Ishimoto’s moment.

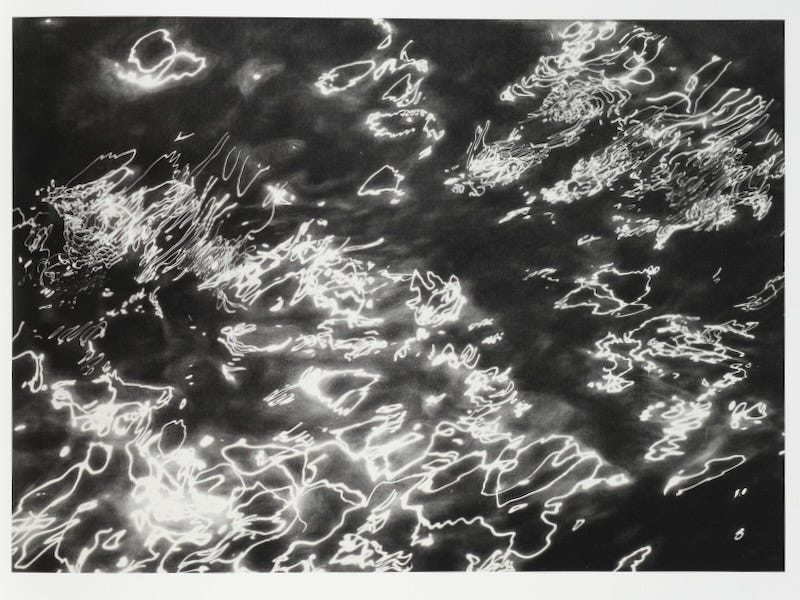

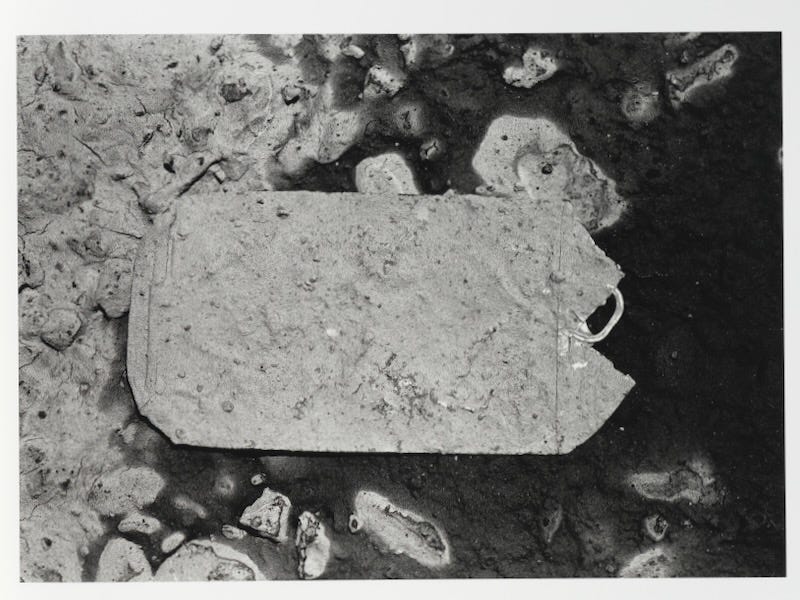

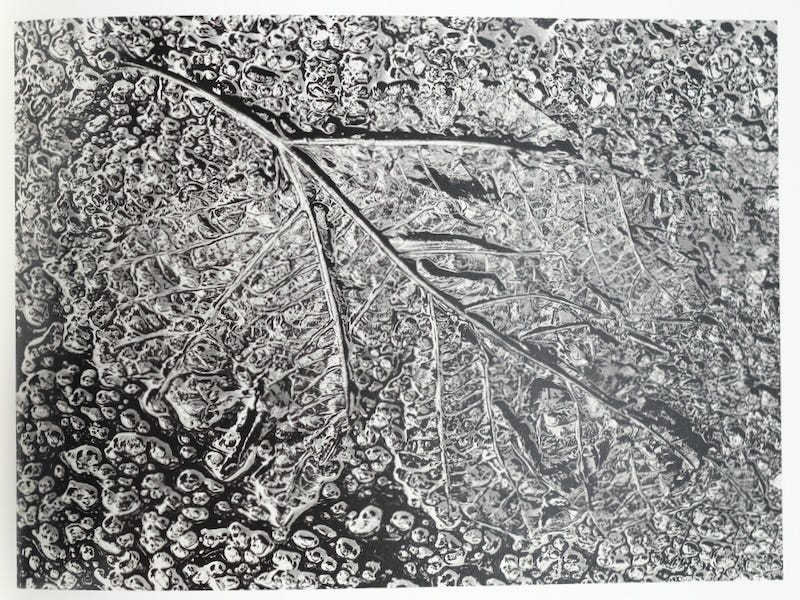

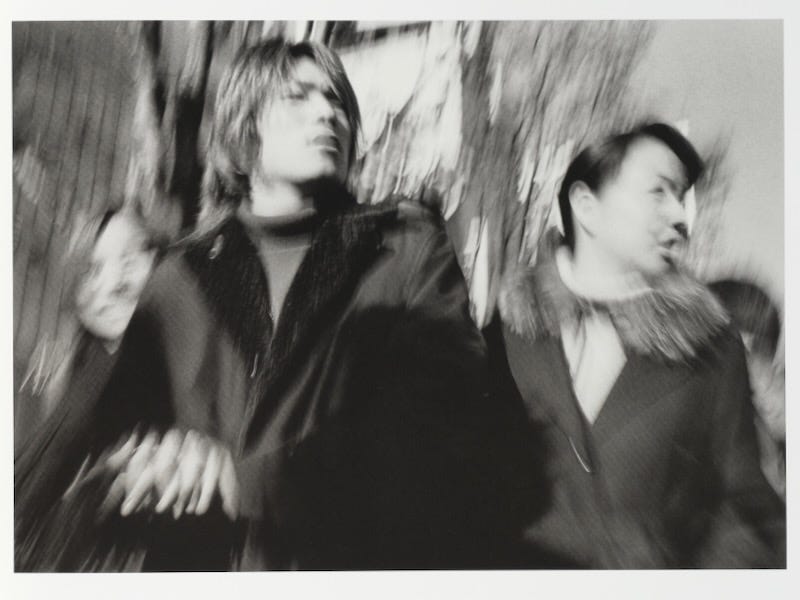

Published in 2004, this lushly produced book consists of six rhythmically intertwined subjects: crushed cans disintegrating into the asphalt; fallen and decaying leaves; footprints melting in the snow; flowing water; clouds; and people on the street. All told, the book contains around two hundred photographs.

Are the photos beautiful? Of course they are. They’re Ishimoto’s.

Yasuhiro Ishimoto was born in the United States in 1921. He moved to Japan when he was three, and began photographing when he was 10 years old. In 1939 he returned to the United States, perhaps to avoid being drafted into Japanese military service. In 1942, the U.S. government incarcerated him in the Amache concentration camp.

Upon his release, Ishimoto moved to Chicago, where he studied at the Institute of Design: first architecture, then photography with Harry Callahan and Aaron Siskind. For a time following his graduation, he moved back and forth between the United States and Japan. His Mondrian-like photographs of the Katsura Imperial Villa taken during this period are frequently credited with introducing a new modernist sensibility to the Japanese photography world. He also produced the classic photobooks, Someday, Somewhere (1958) and Chicago, Chicago (1969), the second one published in the same year that he took up Japanese citizenship and settled permanently in Japan. Despite ultimately choosing Japan as his home, Ishimoto frequently stated that there was no Japanese influence in his photography.

Ishimoto has never quite escaped those two photobooks, just as Robert Frank never escaped The Americans. Though his work is more formally structured, Ishimoto, like Frank, had an outsider’s eye for America, and turned it to questions of race and class, though perhaps somewhat more compassionately. But Ishimoto also has published books photographing flowers, sculptures, architecture (he partially made his living as an architectural photographer), and myriad other subjects.

Ishimoto began photographing the leaves, the cans, the clouds, and the footprints some twenty years prior to the publication of the book. Some have been the subject of exhibitions and smaller publications. The rippling water was a later addition, and the photos of people came after.

Ishimoto was, largely, a photographer of cities. The photographs in moment are, in a sense, urban photographs, the subjects not arranged, but taken as he found them. The photos of water were all taken at the river that flowed by Ishimoto’s Tokyo home, and the clouds were photographed from his window.

Yet nothing in the content of the photographs gives a clue as to their specific location. The cans are mostly so far disintegrated as to be lacking any logos. Faces are perhaps vaguely Asian, but little more can be said. The photos often verge on the abstract, but they are nevertheless very much photos of the object itself, not, say, representations of emotion in the way of Stieglitz’s Equivalents.

There is no single image that stands out. It is a book built on repetition without narrative. Everything disappears—more often than not into the earth, so most of these photos are taken looking downward. Ishimoto writes in the afterword: “All living things eventually fade away. People have been saying this since language first began. I thought I understood that years ago, but it was only an intellectual understanding. Now I am more than 80, confronted with a reality I can no longer escape.”

Yet, that is too easy. These photos are not simply about transience but also about individuality. Each leaf is different, and the framing is mindful of the differences. The clouds intrigue me. These are not the elegant clouds of William Eggleston, these are the everyday, almost formless clouds of the city. Pause, and observe. Are they really disappearing? Or are they simply in the process of becoming something else?

Photos are but a memory. After the moment passes, the subject of the photograph will already have changed, each one according to its own timescale.

The foreword to the book takes the form of a four-page long prose poem written by Takashi Tsuji. Like all text in the book, it appears in both Japanese and English. (I am reminded of Kawada Kikuji’s The Map, and its bilingual prose poem by Kenzaburo Oe. Surely this is not a coincidence.)

An excerpt from Tsuji’s poem:

There are people who seek explanations.

They want to know why the photographer is so fond

Of that ancient essay, The Ten-Foot-Square Hut.

Theorists question the crushed cans, fallen leaves,

Ephemeral ripples and floating clouds.

Some people want to analyze until they find an answer.

The flotsam of this world.

It is right there, close to you.

Things seen for the first time seem fleetingly familiar.

Stop and hold back your imagination,

It would seem that the flotsam of this world is all there is.

But that cannot be true.

Is The Ten-Foot-Square Hut—the Hōjōki, written more than 800 years ago by the Japanese poet Kamo no Chōmei—the key to understanding Ishimoto’s book? I open Donald Keene’s translation and begin:

The flow of the river is ceaseless and its water never the same. The bubbles that float in the pools, now vanishing, now forming, are not of long duration: so in the world are man and his dwellings.

I linger on Ishimoto’s photos of people. These photos were shot with a long exposure without a viewfinder. From the hip, with an instinct for long exposure. How different that is from Ishimoto’s usual method of carefully studying light and weather, of perfectly framing and exposing photographs. These happenstance souls, scattered through the book’s pages, seem to me caught in a transformation between the physical and something else. A double foldout in the center dedicated to this group suggests that these photos are central to the book’s message. Each of us will also disintegrate, disappear.

Yasuhiro Ishimoto died in 2012, at the age of 90. He donated his archive of more than 7,000 prints to the Museum of Art in Kochi, Japan, where he had spent much of his childhood.

Thank you for reading,

Joel