Dear Friends,

Here in Japan, we’re coming to the end of a string of holidays that are together known as “Golden Week.” I spent a good chunk of it at middle school baseball camp with my son. The training camp was managed and staffed by parents, and my job was to photograph everything, all of the time, from breakfast each day at 7 am until lights out. It was a great time and I came home exhausted.

It’s hard to believe how much has happened this year. In recent newsletters, I have discussed my new book, Restrooms, an exhibition I was in at the giant CP+ trade show, and an exhibition I am currently in at the Haeden Museum in Korea. In case you missed those newsletters, do follow those links to learn about what I’ve been up to.

In this newsletter, I would like to turn back to discussing Japanese photography, and to share one of my favorite classic books—Where Time Has Vanished, by Ikko Narahara. If this interests you, read on! If not, I’ll be back with more personal news soon.

Where Time Has Vanished was published originally in 1975, and then again as a revised version in 1997 with additional photos. I found my copy of the first edition in a second-hand book shop in Tokyo that specializes in old comics. They must not have been aware that, online, used copies can sell for around 500 dollars; mine cost less than a tenth of that. It is a large book, about 33 centimeters square and weighing nearly four kilograms with the slipcase. The paper is of the highest quality, and, nearly fifty years later, shows very little signs of aging.

Ikko is one of two Japanese photographers to be generally known on a first name basis (indeed, his first name is blazoned across the cover of the book), and by many Japanese photographers he is more highly regarded than Daido. His 1956 debut exhibition, Human Land, is among the most important in Japanese photo history. Along with Kikuji Kawada, Eikoh Hosoe, Shomei Tomatsu, and others, he founded the VIVO collective in 1959. In the 1970s, he was at the height of his powers and living in the United States. He had had some nine one-man exhibitions in Japan, published five books, and won numerous major awards, including Photographer of the Year from the Japan Photo Critics Association.

Many of the photos in this book were taken while Ikko was driving from the East coast of America to the West in 1972, camping along the way. (A few others, taken while in New York, provide a lighter touch and some breathing room.)

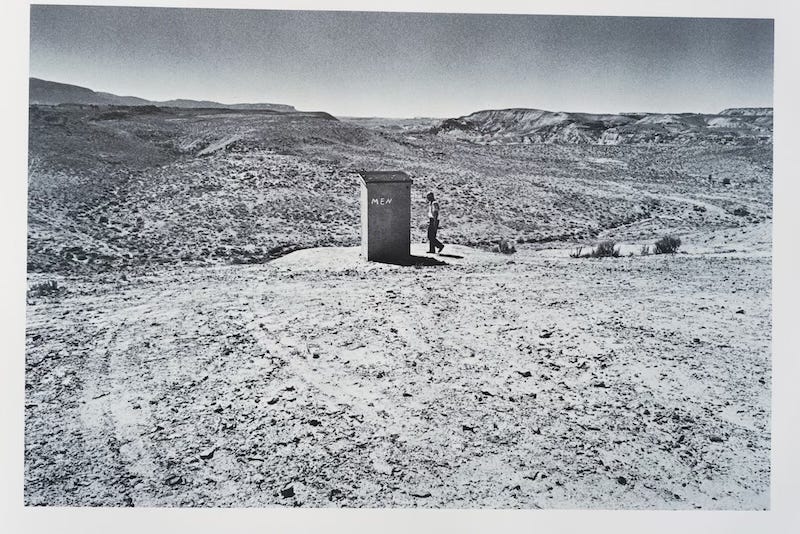

Despite the classic road trip, Ikko has only a little to say about America—but quite a lot to say about his own inner world and his relationship to the universe. His photos have a surreal, end-of-the-world quality, a feeling this book shares with Trent Parke’s Monument. (Kikuji Kawada’s Los Caprichos also come to mind.) Humans are largely absent, but when they appear, they are often ethereal: a girl peering out of a camper window, the reflected ghost of a bus driver on the Wyoming plains. Almost everywhere, the skies are dark and menacing.

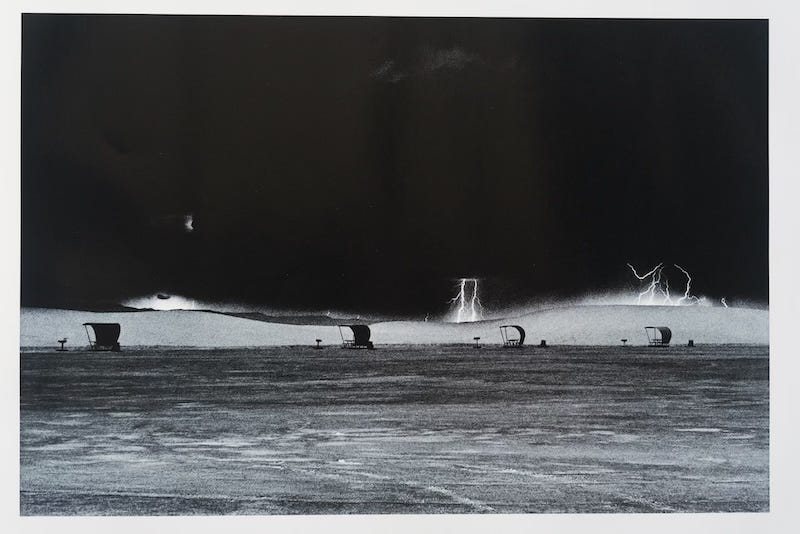

Ikko was a boy during World War II. Though this is not a book of social criticism, when looking at his image of lightning strikes over White Sands, one cannot help but thinking of America’s testing of the nuclear bomb. A balloon being launched at Cape Kennedy, Florida, closely resembles the Fat Man bomb detonated over Nagasaki. In the long essay which closes the book, Ikko meditates on his childhood, World War II, American Indians, the communication of trees, hippies, the Apollo mission, and much else.

It is often noted that in 1970, Ikko took a class with Diane Arbus. I have a hard time feeling any of her influence in this book. The two photographers share a psychological intensity, but by this time, Ikko seemed uninterested in portraiture or humanity, instead searching out mythic moments.

“While we were driving across there flat Arizona desert, we felt as though we had been thrown out from the earth and thrust into another planet…. The landscape surrounding us there in the desert was ancient, but to be so informed of the age of something in geological terms is somewhat meaningless. For when one personally experiences the image, it is something altogether different and new as though it were just born. And so it was for us.”

To capture the sensation, Ikko uses flash, filters, wide lenses, and slow shutter speed. While the photos are often grainy, the careful compositions bear little resemblance to the snapshot aesthetic that is often associated with Japanese photographers of the era. The tinge of surrealism, and indeed, the pacing of the book, remind me more of Koudelka’s Exiles, though these are frequently colder, harder photos.

Then, after exactly 100 black and white images, the book suddenly ends with a singular color photograph, of the Apollo 17 launch in Florida. About seeing that launch, Ikko concludes: “on that historic occasion, I had a feeling about myself, that all my life and my effort heretofore had brought me to this point where my personal world and the world of the universe met and joined hands.”

I’ll wrap up with a spot of photo news. I mentioned Ikko Narahara’s VIVO Collective co-founder, Kikuji Kawada. If you’re in Tokyo currently, I recommend swinging by PGI Gallery to see Los Caprichos, Demon of Tomorrow, the lates in an ongoing series of photographs by Kikuji Kawada.

The big photography event in Japan right now is the annual Kyotographie festival in Tokyo. This year’s installment has been well reviewed. It runs for one more week, and has been well reviewed. I have been too busy to make it down there this year, but keeping busy is good.

And with that, I’ll be back in a month or so. Feel free to pass this newsletter on!

Joel